and colleagues suggest the answer is climbing. The authors reject the traditional view of wing evolution in birds as either

, and suggest a third, up-a-rock model. They used the

as a model because it is a ground bird that prefers to use wing-assisted incline running or

to flying in gaining higher ground, and has precocial development(a trait that is thought to be shared with birds' dinosaur ancestors. They then record various activities of chukar chicks and adults.

The authors criticize the tree-down and ground-up models as both limited and unsupported. The tree-down model, they argue, is not a clear and logical explanation for how wings for gliding could have evolved for flying. They suggest the current examples of gliding by vertebrates, such as squirrels with extra skin who glide form limb to limb and to avoid injury during falls, are sufficient for an arboreal environment and show no inclination to need or that they would gain an advantage by the adaptation of flight. The ground-up hypothesis is even less likely say the authors, the idea that proto-wings were used to accelerate running seems unlikely when no bipedal organism currently uses that strategy.

I think their point on the flaws with the tree-down hypothesis demonstrates how hypotheses for the evolution of characters are weakened when they lack a way to support them through observation, experimental, or correlative methods. An explanation for how and why a feature came to evolve needs more than just an intuitive guess. I think they made an even better argument with the weakness of ground-up because if using wings or proto-wings to increase speed was advantageous, it would seem that some of the extant fast running, bipedal birds like the ostrich would employ it, rather than tucking its wings out of the way. Also, flapping arms\proto-wings\wings to gain speed would be energetically costly and would only be advantageous in that it allowed the organism to run faster than its prey/predator, thus I think the use of arms\proto-wings\wings for acceleration is overkill.

Fairly recently, certain ground birds have been discovered to use their wings to run up steep inclines, even at ninety degree angles. This is called wing-assisted incline running (WAIR) and is preferentially used to flying when the terrain makes it possible. Because chukars are ground dwelling, they have powerful leg muscles that are capable of sustained work. Though chukars are fully capable of flight, their wings are dependent on anaerobic energy and they tire easily. WAIR is thought to be an energy efficient means of escape for the ground birds that exhibit it. The authors argue (as a few have before them) that WAIR is a good model for the transient stages of flight and that it shows a gradient of adaptation that gives a possible explanation to how wings capable of full flight arose.

The authors tested the wing stroke and the force generated during WAIR with adult chukars. They found that the wing stroke was similar to a flying stroke, but rotated so the force pulls the bird toward the substrate and slightly upwards, increasing traction and adding some propulsion. They also showed that the majority of the ascension was powered by the legs. Then, they used day old to adult chukars to simulate the use of WAIR with less developed wings to those that can fly. Chukar chicks are incapable of true flight until they are seven or eight days old, though they can run soon after hatching. They reach their full flight capabilities by seventy days. The authors tested WAIR ability as the chukars were growing up. In some of the chicks, they plucked out the wing flight feathers, in others, they trimmed the feathers to half their size, and some they left intact. Though the intact birds did WAIR best and the plucked birds worst, all used WAIR to get to elevated areas. They authors also found that chukars start with symmetrical flight feathers before later developing their asymmetrical flight feathers usually seen in adult birds. Though symmetrical feathers are often thought to have no aerodynamic value and not meant for flight, birds in this stage are capable of creating aerodynamic force to ascend steeper inclines then they could otherwise do.

Because the developing feathers and bodies of young birds can give insight into transitional forms of flight, this experiment did well in using developing birds. Also, by using modified wings, they showed that even a proto-wing with the less derived symmetrical feathers could be useful in WAIR for escaping predators. By showing that the wing stroke during WAIR could be modified for flight by simply rotating it, they support their clam that WAIR could represent a transitional step. Though the wing stroke during WAIR may be a precursor to flight, the authors didn’t mention that the similarity might exist because WAIR may have come after fully flight, rotating the wing stroke from that of propulsion through the air, to up a cliff.

The experiments done by the authors furthered the understanding of WAIR and made a decent argument for it being the transitional step to flight. That WAIR can be used by modified wings, useless for flight, as well as wings capable of flight demonstrates a possible transition from a flightless ground bird, to one that is capable of powered flight. That the authors demonstrated that a symmetrical feather can be aerodynamically useful might also lead to a reinterpretation of the fossil record, where birds with symmetrical feathers were often assumed to be flightless. The article is also a call to base ideas on possible functions of transitional forms on evidence from many disciplines such as life history, and development to achieve a more holistic and complete model rather than one based on some evidence but with guesswork filling in the blanks.

[Editor's note: Ken Dial and colleagues have recently published another paper in Nature (which Emily must've have missed) where they tested their theory further, by focusing specifically on wing-stroke kinematics. You can download the article and read more about this work from Dial's website - Madhu Katti]

Reference:

Dial, K.P., Randall, R.J., Dial, T.R. (2006). What Use Is Half a Wing in the Ecology and Evolution of Birds?. BioScience, 56(5), 437. DOI: 10.1641/0006-3568(2006)056[0437:WUIHAW]2.0.CO;2

Dial, K.P., Jackson, B.E., Segre, P. (2008). A fundamental avian wing-stroke provides a new perspective on the evolution of flight. Nature, 451(7181), 985-989. DOI: 10.1038/nature06517

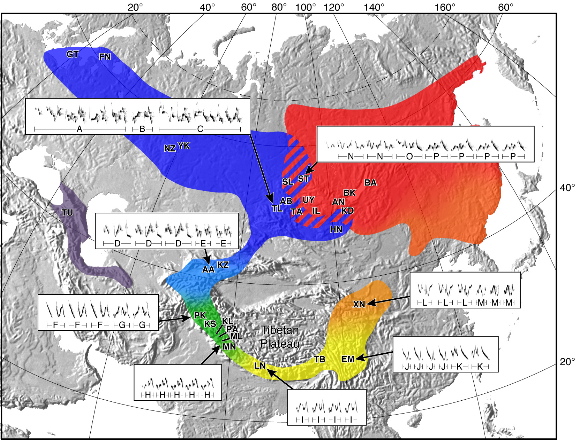

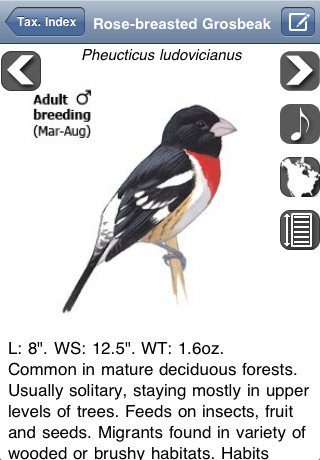

This is a well written and studied article. This article was about the evolutionary divergence of the Siberian green warbler. The evidence they gather for their thesis is overwhelmingly convincing and they seemed to cover all questions that may come up. They believed and tested that the divergence of song may be the main cause of speciation. This is a highly feasible theory because if you can’t understand someone it is hard to breed with them. (Continues below...)

This is a well written and studied article. This article was about the evolutionary divergence of the Siberian green warbler. The evidence they gather for their thesis is overwhelmingly convincing and they seemed to cover all questions that may come up. They believed and tested that the divergence of song may be the main cause of speciation. This is a highly feasible theory because if you can’t understand someone it is hard to breed with them. (Continues below...)